When Angela Mapes Turner’s daughter was in fourth grade, she was assigned a class project on a notable Hoosier. She hoped to spotlight her great-grandfather, Arthur Mapes — a poet known for writing Indiana state poems and designated as the state’s “poet laureate.”

But her teacher advised against it. Without official sources to support his significance, and relying on family accounts, the project wouldn’t meet the assignments criteria. So instead, she chose another famous Indiana poet, James Whitcomb Riley.

A few years down the road, Mapes Turner began the application process to secure a historical marker honoring her grandfather. She didn’t expect the journey to become so meaningful, she said. After family members combed through archives and compiled research, they submitted an application to the Indiana Historical Marker Program.

Now, future students researching notable Hoosiers will have an official source to cite.

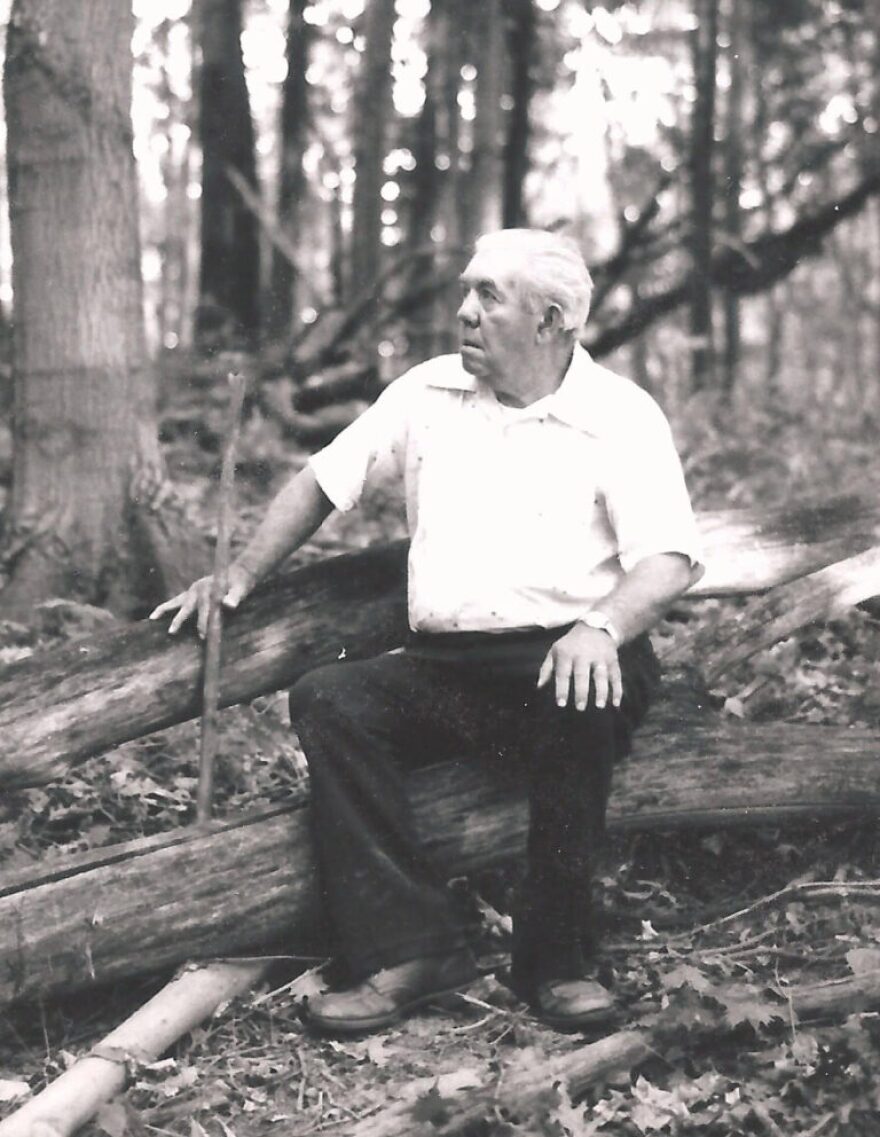

Arthur Mapes will soon be recognized with a state historical marker, featuring the familiar blue enamel background and raised gold lettering. It’ll be nestled in the trails of Bixler Lake Park in Kendallville, a place where he grew up and wandered the woods, drawing inspiration for his poetry.

“The Indiana Historical Bureau, acknowledging that it does have statewide impact, was meaningful to me and to our family,” Mapes Turner said. “Just to know that it’s literally going to be cast in iron for future generations to see the permanence of it is really special to us.”

Mapes’ marker is close to production, though the program is in transition. In June, Indiana agencies laid off dozens of state employees in response to recently enacted budget cuts. Some of the deepest cuts appeared at the Indiana Historical Bureau, a division of the Indiana State Library.

Five of the bureau’s six employees were let go without advance notice — leaving one person to run the office and manage the markers.

“Historical markers provide snapshots and tangible reminders of our state and nation’s past,” Director Casey Pfeiffer said. “… Even with over 750 markers, we have just barely scratched the surface of the stories that could be shared.”

The marker program

The Indiana State Historical Marker Program began in 1946, with the first marker placed in December of that year highlighting the Indiana State Capitol.

David Steele, managing principal of the Steele Group, has successfully placed five historical markers in the near south side of Indianapolis. He calls the state’s historical marker program the “best-kept secret in the state government.”

Out of Steele’s five markers, he said he is particularly proud of a marker honoring Leedy Manufacturing, a factory known for creating Purdue University’s “World’s Largest Drum,” and the vibraphone.

“That’s one of the coolest stories of a manufacturing company in the city,” Steele said.

He also placed markers honoring German immigrant communities including early drugstore founder, John Hook. Growing up in Fountain Square, Steele said he rarely saw historical markers in his neighborhood. But when traveling to areas like Meridian Hills or the old north side of Indianapolis, there were always historical markers.

So years later down the road, Steele became interested in highlighting the neighborhood he grew up in, and the key Indiana historical aspects of the near South Side that no one knew about.

Since historical markers are not amenable to revision, marker texts are thoroughly documented with primary source material. Steele said what attracted him to the marker program the most was the research that goes into each marker.

A friend told Steele to do a marker on Meredith Nicholson, an author known for writing the book “The House a Thousand Candles.” He said if you go to his home, there is a small local marker saying that he lived there.

When Steele dove into city records of when he was supposed to live there, he could not find Nicholson listed anywhere. Indiana architecture experts helped him find that Nicholson was a poor writer who married into money — the house was bought by his wife and listed in her maiden name. They even tracked it down to where she transferred the deed to her husband.

“Those are things that make this marker program so legitimate,” Steele said.

Legacy in metal

Each of the markers is crafted by Sewah Studios, a century-old company based in Marietta, Ohio. Company President Bradford Smith said Indiana is one of the leading marker programs and is one of the oldest Sewah Studios state partnerships out of the 44 states that they work with.

“We’ve been honored to feature them as one of our top programs across the country. They are definitely important to us,” he said.

Smith said they create every marker by hand with a 100-year-old process. He said typically it takes about three weeks to produce the marker and ship it to Indiana.

Smith compared production to minting a coin. He said it goes through five phases, starting with typesetting, moving to a cast aluminum foundry to make marker impressions, then to a finishing department, followed by a powder-coating process. Last is decorating the letters with gold lettering and adding the iconic aluminum rail. The marker is finished with a protective clear coat to give it a wet-looking professional finish.

“When you see that blue marker with the original rails, Indiana outline, it’s just an iconic feature for all Indianans’ to be proud of,” Smith said.

Each of the markers costs $3,300 to produce and install — typically paid for through private funding. Mapes’ marker, for instance, was fully funded by his former employer, Flint & Walling Inc., with the Kendallville Parks Department volunteering to install it.

Choosing the marker’s location wasn’t easy, Mapes Turner said. The family ultimately selected Bixler Lake Park, where Mapes spent his childhood walking trails and hunting small game to feed his family during the Great Depression. A bench nearby already honors him and his wife.

“I think my grandfather wouldn’t believe this,” she said. “He was a humble man who worked in a factory, but loved the beauty of words. For the state to honor that now — decades after his poem — it’s incredibly special.”

Uncovering forgotten histories

Pfeiffer said markers run the gamut from state history, arts, sports and agriculture to science, medicine, business and military history.

Interest in the marker program has grown in recent years, with an increase starting in 2016 due to the state’s bicentennial and a renewed interest in preserving the state’s history, she said.

Over the past four years, Pfeiffer said the program has received more than 30 applications annually and has approved 16-19 markers each of those years. So far in 2025, the bureau has helped dedicate seven markers.

Some markers elevate untold stories — especially those omitted from textbooks.

Eunice Trotter, Black heritage preservation program director for Indiana Landmarks and Historic Preservation, has helped erect 15 markers around the state in three years. One honoring Mary Bateman Clark, a formerly enslaved woman whose 1821 court case helped end indentured servants in Indiana, is posted outside of the Knox County Courthouse.

Trotter said the marker is one of the few markers memorializing Black heritage in the community. With her own research, she was able to preserve contributions and the presence of Black Americans in pre-statehood Indiana.

“That case was found in 1821, so nobody would have known that it’s a case that should have been included in Indiana state history classes,” she said. “It still isn’t really included to the state, so it’s the only reminder of that history we have.”

Trotter said her organization typically hires researchers to dive deep into the history that’s required for a marker — like a case from the 1920s when Black children in Lyles Station in Gibson County, were subjected to harmful radiation experiments to treat ringworm.

Many of those children suffered lifelong damage. Trotter is now pushing for a marker to honor them, especially after a lawsuit was filed and dismissed, and the children were left with no compensation.

A 2009 movie titled “Hole in the Head: A Life Revealed” tells the story of a child that was affected.

“It’s the kind of work that we’re doing seeks to uncover, document and preserve or restore Black History heritage sites,” Trotter said. “This is history and sites that are little-known, but they are there, just waiting to be uncovered. And there’s just so much history that we don’t know so fast. You know, it just gets overwhelming thinking about it,” Trotter said.

“Markers are the way to give a snippet of important history that might otherwise not be known,” she added.

And sometimes they include history that isn’t pleasant.

Trotter mentioned a marker that tells the story of John Tucker’s lynching in Indianapolis. It was placed in 2023.

Another marker notes the history of Indiana’s 1907 eugenics law, which authorized a forced sterilization program “to prevent procreation of confirmed criminals, idiots, imbeciles and rapists” in state institutions. It was placed in 2017.

Meanwhile, some markers have been vandalized, stolen or run over — like the Calvin Fletcher marker in Indianapolis, which was replaced after three years of fundraising, only to be run down again. Fletcher opposed slavery and promoted organization of U.S. colored troops in Indiana in Civil War, according to his marker.

Indiana Capital Chronicle is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Indiana Capital Chronicle maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Niki Kelly for questions: info@indianacapitalchronicle.com.