Forester Perry Seitzinger showed visitors a deep part of the forest. Here, sunlight reaches the ground. The woods are obscured in shadow. Three years ago, the Forest Service clear-cut this area.

“They removed all the overstory and let the natural seed bank take off and regenerate into hardwood trees,” Seitzinger said.

The Forest Service wants to restore the oak and hickory forests that once covered Indiana before settlers clear-cut the state. It’s targeting two areas: the Houston South Project and the Buffalo Springs Project.

The Forest Service uses a combination of low-intensity prescribed fire burns and cutting down some trees. That creates conditions benefiting oak and hickory over other trees.

“I must admit, when this first happens, it is not aesthetically pleasing whatsoever, and that elicits an emotional response in people,” Seitzinger said. “It's important to know the science behind it, and why we were doing what we do.”

The Forest Service did not grant an interview, but Seitzinger, a private consultant, explained its process.

“If we don't have any forest management, we will not have our forests as we know them because of invasive species and changes in climate and those sorts of things,” he said. “A passive approach to managing our forests is no longer a valid option.”

Forest Service ecologists say taking no action would continue the trend toward shadier forests dominated by maple and beech.

“The intent of what was done here was looking forward to what's going to be here in 100 years,” Seitzinger said. “That timeline in and of itself is difficult for people to grasp.”

Mike Stambaugh, an associate professor of forest ecology at the University of Missouri, looked at the agency’s plan to bring disturbances to Hoosier National Forest.

“The Forest Service projects I've reviewed and seen, they're using all that information to make these decisions,” he said. “I think it's all extremely well founded, in my opinion.”

An oak-hickory forest without a dense canopy of other trees creates habitat for turkey and songbirds that prefer open forests. It also allows a variety of sunlight-dependent wildflowers to flourish.

Those seeds can lie dormant for decades, but without the right conditions they can die.

“The clock's going to run out on being able to bring these species out of the seed bank,” Stambaugh said. “I think they're probably on those types of sites trying to maximize the site potential.”

Hands off the forest

But restoring an ecosystem is messy. Burns and cuts come at the short-term expense of other species, and they’re off-putting to some who live by, and enjoy, those forests.

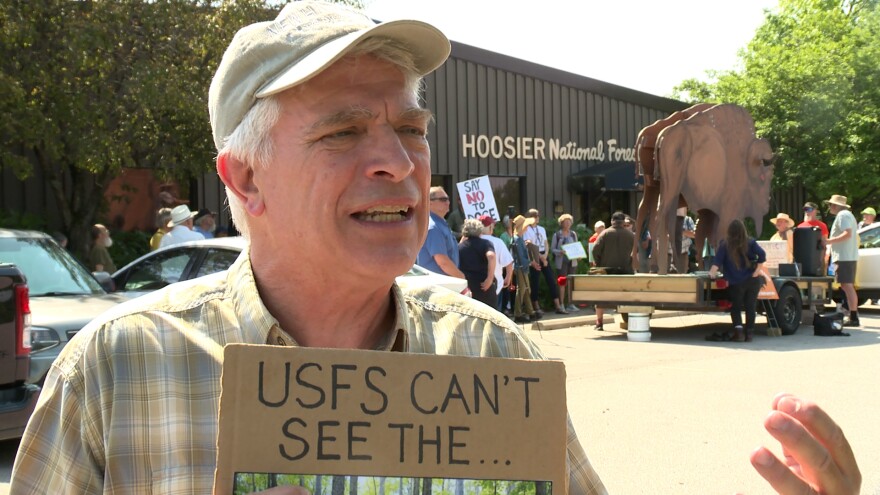

The Indiana Forest Alliance and its giant plywood bison are a frequent presence at protests against the Buffalo Springs and Houston South projects. Many of its supporters, such as horseback rider June Spencer, have seen recently clear-cut areas firsthand.

“There's trees, and brooks, and hills, and it's just nature and good friends to ride with until you get to where they've clear cut timber out, and then it's an ugly mess,” she said.

The Forest Alliance advocates for a hands-off approach, what ecologists sometimes call “preservation,” versus involved management or “conservation.”

The Forest Alliance’s founder and former executive director Jeff Stant has fought for the forest for nearly 50 years, since he helped establish the Charles Deam Wilderness. But his organization is often at odds with the government service established to protect it.

“Now that land has slowly healed, and so the natural, much more diverse forest is coming back,” Stant said. “We think that they should manage the Hoosier National Forest to let that natural transition occur.”

Stant worries about the effects of burns and cuts on erosion and water quality, as well as the loss of habitat for species of birds and bats. The Forest Alliance has taken water samples in Patoka Lake near some of the burns but hasn’t yet released the results. The Forest Service has said it’s confident its project won’t harm water quality.

“They're going out of their way to do the projects in a way that are going to cause major impacts,” Stant said. “All you have to do is look at the three square miles they just burned and all the hazard trees they cut down to know they're doing that.”

Friends in high places

The Forest Alliance, Monroe County Commissioners and other environmentalist groups have sued to block one of the two projects, Houston South, near Lake Monroe.

But they also have what might seem like an unlikely political ally: Indiana’s Republican Governor Mike Braun.

He’s written two letters to the Forest Service, a federal agency, asking it to end the projects, citing local opposition and saying it threatens the forest’s “recreational and ecological value.” He also wrote a letter of support to opposition groups.

Stant said he first met Braun around a decade ago when he was a state legislator and the two worked together to reduce logging in state forests.

Despite being a lifelong Democrat, Stant and his wife donated $66,000 to Braun’s bid for governor.

“I was glad to see him win the primary resoundingly, and quite frankly, he has a vision about the public lands that I don't think the Democrats had even thought about yet. So I was glad to support him as governor,” Stant said.

As a senator, Braun sponsored legislation to create a new wilderness area including northern parts of the forest. That bill never made it off the ground.

Besides his love of outdoor recreation, the Indiana governor is also one of the largest timberland owners in the state, with thousands of acres near Forest Service projects, collectively worth tens of millions of dollars. Wood harvested on his land enters the same market as timber sold by the Forest Service.

Story continues below map

As a state legislator, Braun attempted to limit logging in state forests while successfully cutting taxes and regulations on private timber.

The governor’s office did not respond for an interview.

“I don't think he has a conflict of interest. I know he's been accused of that, because he owns private woodlands, he doesn't want the government competing,” Stant said. “I don't think the government selling logs hurts him at all from an economic standpoint.”

But Braun, a Jasper native, is in the same camp as many in the region he was raised. Hunters, hikers and horseback riders use the forest, and many don’t want to see it change.

When it comes to passive versus active management, Stambaugh said what seems right can be immensely personal.

“No one's right there,” he said. “It’s your kind of philosophy, and in some cases, it even comes down to environmental ethics, like what's right and wrong.”