Indiana leaders gathered Thursday to consider how the state could mine its ample coal waste for the rare earth elements key to modern technology — in a bid to boost domestic production and break China’s dominance.

“I want all these liabilities that we’ve got to turn into resources,” Kit Turpin, director of the state’s Abandoned Mine Land Program, told the Indiana Rare Earth Recovery Council at its first meeting.

Gov. Mike Braun created the group in an April executive order. He directed its 13 members to help develop a coal waste-based rare earths industry.

The 17 metallic elements are critical to defense, health care, power generation, transportation and other industries. They’re also in widely used consumer products, like iPhones and LED lights.

Despite their name, the elements aren’t actually rare — they’re just typically “finely dispersed,” rarely found concentrated enough to easily extract.

Major deposits are found in China — the world’s leading rare earths producer — as well as Brazil, Russia, and elsewhere, said Maria Mastalerz, a research geologist for the Indiana Geological and Water Survey.

Federal estimates place the U.S. at just 1 million metric tons of reserves, compared to global reserves of about 120 million metric tons.

“Indiana does not have traditional sources” of rare earths, Mastalerz said.

But coal and its production byproducts — gob, slurry, spent substrate, acid drainage and sludge, and more — could be “unconventional” sources.

Tapping coal

“Every point” of mining, processing and using coal presents “special” opportunities to recover rare earths, according to Mastalerz.

However, these materials are “low-grade,” with lower concentrations of rare earths, she repeatedly cautioned.

That makes extraction more difficult and expensive.

Mastalerz — who specializes in coal geology, organic petrology and geochemistry — is testing ways to find rare earth “sweet spots” and “optimize” their recovery.

The materials are plentiful, though.

Turpin, whose Department of Natural Resources program rehabilitates abandoned mine lands, said Indiana has more than 1,900 sites. The program has almost $80 million worth of projects in the pipeline, but there’s an estimated $400 million worth of unfunded inventory, he said.

“The economics don’t look good” for rare earths recovery, he said, “but if you already have a problem (in abandoned mine lands) that needs addressed, maybe you can find efficiencies.”

The program tested a gob pile and found dozens of elements, including rare earths and other critical minerals, per Turpin.

“Every cubic yard of coal refuse out there contains about 10 grams of yttrium — what’s in your hand there,” Turpin said, as council members passed around a small case with chunks of lustrous metal.

“The problem with it is … you’re talking about processing a ton of this material for that 10 grams,” he told them.

The gob pile has an estimated $10 billion worth of rubidium in it, he added, but it’s stuck in 2 million yards of material.

The program must use its largely federal funding on mine land reclamation, however. Rare earths recovery has to be “incidental” — another challenge.

‘Your test state’

Federal officials called in from Washington, D.C., to praise Indiana.

“The things that you’re doing are the same things that we would like to do,” said Lanny Erdos, director of the U.S. Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement.

“We really are with you in your efforts here,” said Ned Mamula, director of the U.S. Geological Survey. “… We want to change our thinking about this. Pile of waste? No. … There’s products in there. We’ve got to find a way to get them out.”

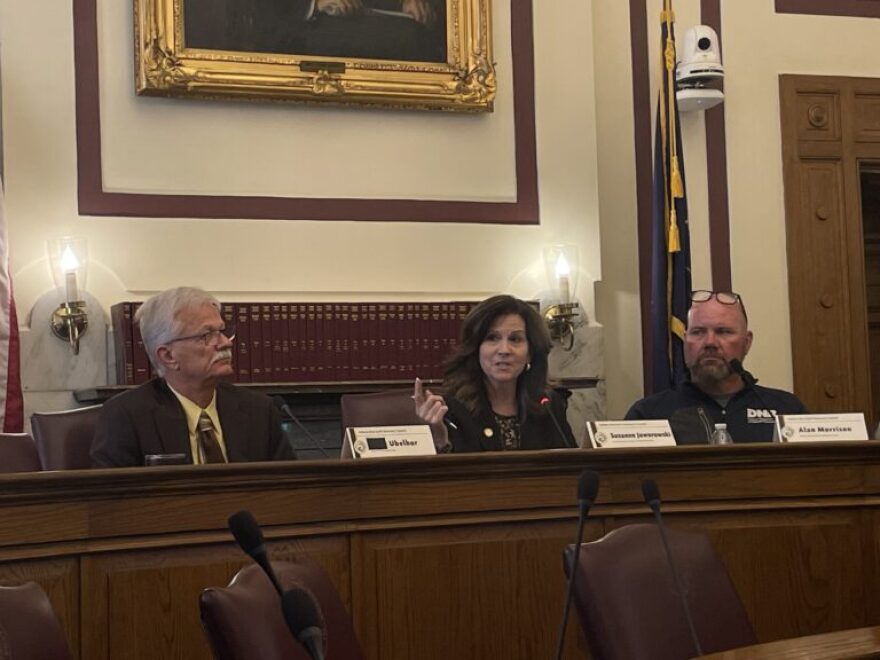

Indiana Secretary of Energy and Natural Resources Suzanne Jaworowski thanked the pair, telling them, “Keep in mind, we’d like to be your test state — a beta — and definitely your partner here. So we’ll keep you updated on our activities.”

Braun’s order includes several directives for the council: advance a coal site cleanup program, collaborate with industry on extraction and processing technology, establish Indiana-based supply and refinery operations, and work with educational institutions to create an extraction and processing workforce program.

The group has to provide annual updates to the governor, and a final report is due before the end of 2026.

The next meeting date hasn’t yet been set. Council members suggested bringing in industry representatives, like those interested in processing rare earths out of coal waste or those who’d use the elements in their products.

Others recommended calling on more academics, since the technology might not be advanced enough for industry, and to consider recovering the elements from recycled technology.

Indiana has an estimated 57 billion tons of unmined coal but only 17 billion tons are recoverable using current technology, said Tommy Sutton, vice president of surface operations at Hallador Energy’s Sunrise Coal.

Of that recoverable amount, 88% would require underground mining and just 12% could be extracted via surface mining.

“I think we’ve got several years,” Sutton said of the industry, but companies are “competing for the same coal reserves.” He said coal companies are turning to byproducts like methane, sulphur and possibly rare earths.

“What was refuse at one point is now something you can actually use,” he told the council.

Indiana Capital Chronicle is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Indiana Capital Chronicle maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Niki Kelly for questions: info@indianacapitalchronicle.com.